The control over AI development should begin right now and be continuously maintained until a fully mature Superintelligence emerges. To accomplish this task there must be a global organization, which would control AI development over a certain level of intelligence and capability. One candidate for such a body could be the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), established in 1968. It has initiated some ground-breaking research and put forward some interesting proposal at a number of UN events such as the first global meeting on AI and robotics for law enforcement, co-organized with the INTERPOL in Singapore in July 2018 or Joint UNICRI-INTERPOL report on “AI and Robotics for Law Enforcement” published in April 2019.

However, these proposals have remained just that – proposals. Until now (May 2021), there has been no single UN resolution in this area. But even if there had been one, it would have probably faced the same problem, typical of many UN activities – the inability to enforce the UN’s decisions.

In spring 2020, the EU Commission launched a Consultation on implementing significant legislation in controlling the use of AI, in which I have also participated. A year later, the legislation was presented by the European Commission for passing it as the EU law. Considering that a similar but a much simpler legislation – General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) took over two years before it was actually implemented as the law, we may expect several years before this legislation becomes law. As it stands, it goes some way further than I had expected as achievable but not as far as I believe it should have gone.

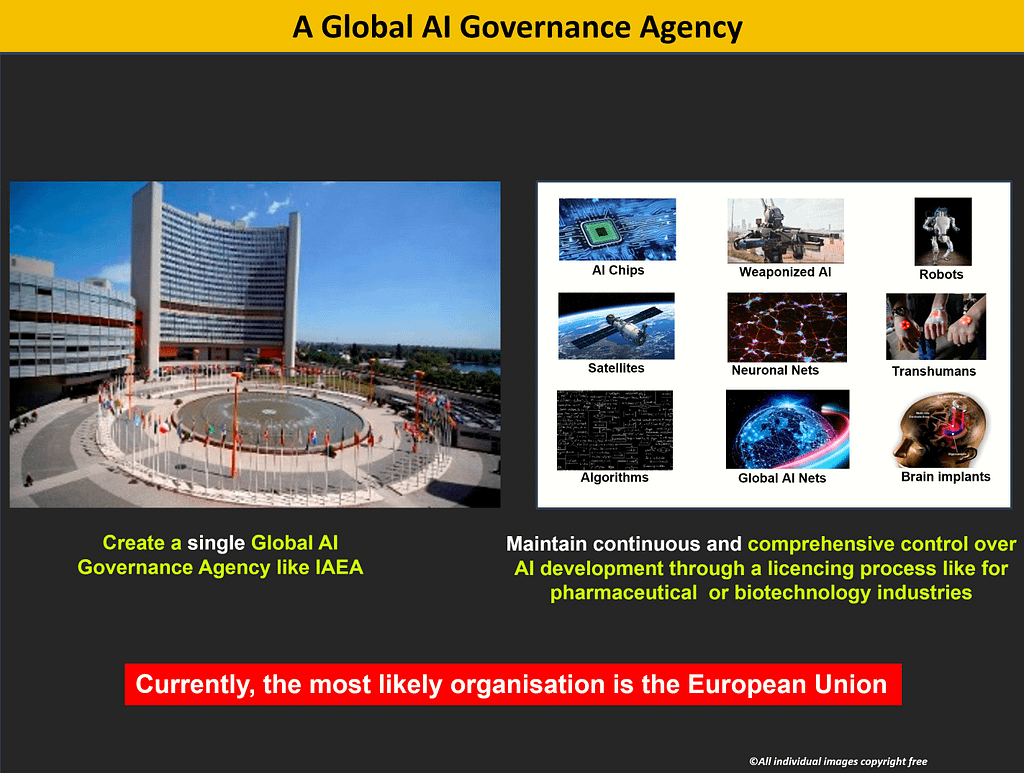

The legislation contains one of the key suggestions in my proposal – to establish a Global AI Governance Agency, which in the document is called the European Artificial Intelligence Board. It will set up the AI risk management standards and monitor their implementation by national competent market surveillance authorities. Additionally, voluntary codes of conduct are proposed for non-high-risk AI to facilitate responsible innovation.

The new standards cover four types of AI risks:

Unacceptable risk: The new law will ban AI systems considered an obvious threat to the safety, livelihoods, and rights of people. This includes AI systems or applications that manipulate human behaviour to circumvent users’ free will (e.g., toys using voice assistance encouraging dangerous behaviour of minors) and systems that allow ‘social scoring’ by governments.

High-risk: AI systems identified as high-risk include AI technology used in:

- (e.g. transport), that could put the life and health of citizens at risk;

- , that may determine the access to education and professional course of someone’s life (e.g. scoring of exams);

- (e.g. AI application in robot-assisted surgery);

- (e.g. CV-sorting software for recruitment procedures);

- (e.g. credit scoring denying citizens opportunity to obtain a loan);

- that may interfere with people’s fundamental rights (e.g. evaluation of the reliability of evidence);

- (e.g. verification of authenticity of travel documents);

- and democratic processes (e.g. applying the law to a concrete set of facts).

This High-risk AI systems will be subject to strict obligations before they can be put on the market:

- feeding the system to minimise risks and discriminatory outcomes;

- providing all information necessary on the system and its purpose for authorities to assess its compliance;

- to the user;

- measures to minimise risk;

In particular, all remote biometric identification systems are considered high risk and subject to strict requirements. This will presumably include brain implants. It is probably the most important part of the legislation since it addresses the real existential threat from AI, which will be much more evident towards the end of this decade. Its rather vague formulation might be useful in the future since it may be easier to expand new type of devices and especially networked systems. Their live use in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement purposes is prohibited in principle. Narrow exceptions are strictly defined and regulated (such as where strictly necessary to search for a missing child, to prevent a specific and imminent terrorist threat or to detect, locate, identify or prosecute a perpetrator or suspect of a serious criminal offence). Such use is subject to authorisation by a judicial or other independent body and to appropriate limits in time, geographic reach and the data bases searched.

Limited risk, i.e. AI systems with specific transparency obligations: When using AI systems such as chatbots, users should be aware that they are interacting with a machine so they can take an informed decision to continue or step back.

Minimal risk: The legal proposal allows the free use of applications such as AI-enabled video games or spam filters. The vast majority of AI systems fall into this category. The draft Regulation does not intervene here, as these AI systems represent only minimal or no risk for citizens’ rights or safety.

Once the EU has established a European Artificial Intelligence Board (EAIB), it should try to engage some of the UN agencies, such as the UNICRI and create a coalition of the willing. In such an arrangement, the UN would pass a respective resolution, leaving to the EU-led Agency the powers of enforcement, initially limited to the EU territory and perhaps to other states that would support such a resolution. The legal enforcement would of course almost invariably be linked to restricting trade in the goods, which do not comply with the laws enacted by the organization, such as the EU. Once the required legislation is in force, it will create a critical mass, as was the case with GDPR, making the Agency a de facto standard legal body with real powers to control the development of AI. This is really good news for the world, although of course much more needs to be done.

The European Artificial Intelligence Board could be responsible for creating and overseeing a safe environment for a decades-long AI development until it matures as Superintelligence. It should act from the start as a de facto global agency in this area and operate in a similar way to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), with sweeping legal powers and means of enforcing its decisions. Its regulations should take precedence over any state’s laws in this area.

However, creating such an Agency must be considered just a starting point in a Road Map for managing the development of a friendly Superintelligence – the earliest and the most important long-term existential risk, which may determine the fate of all humans in just a few decades from now. It is therefore correct, that the new legislation seems to be quite comprehensive in its intended control over all AI products’ hardware and software. That is perhaps why it is vague in some areas. In its current form it will allow it to control the use of robots, AI-chips, brain implants extending humans’ mental and decision-making capabilities – key features of Transhumans, visual and audio equipment, weapons and military equipment, satellites, rockets, etc).

It should also cover the oversight of AI algorithms, AI languages, neuronal nets and brain controlling networks. However, this is still unclear how it can be enforced and applied in the long-term. What is excluded in the current version, is the AI-controlled infrastructure such as power networks, gas and water supplies, stock exchanges etc., as well as the AI-controlled bases on the Moon, and in the next decade, on Mars. There is also a possibility that the pressure of the largest AI companies may actually reduce the scope of EAIB competences.

Some imminent AI scientists, such as Stuart Russell, believe that we may not be capable of controlling advanced AI after 2030. Therefore, we must establish a full global control over the development of AI right now since it will take some time till it becomes fully operational and effective. And here we have a problem. If takes about 3 years for current legislation to come into force, it may be too late because the capabilities of AI change at an exponential pace. Therefore, by about 2025 this legislation may already become obsolete. This is a general problem with political institutions – they still work at best as the pace of change had been the same as in the last century, rather than nearly exponential. This divergence alone may significantly increase existential risks because our civilisation simply cannot adapt quickly enough to the current pace of change.

Any legislation passed by a global AI-Controlling Agency, such as EAIB, should ensure that a maturing AI is taught the Universal Values of Humanity. These values must be derived from an updated version of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, combined with the EU Convention on Human Rights and perhaps other relevant, more recent legal documents in this area. Irrespective of which existing international agreements are used as an input, the final, new Declaration of Human Rights would have to be universally approved if the Universal Values of Humanity are to be truly universal.

However, this is almost certainly not going to happen in this decade. China, Russia, N. Korea, Iran etc. will not accept the supervision of such an agency since they will still aim to achieve an overall control of the world by achieving a supremacy in AI. In any case, such laws should be in place, even if not all countries observe them, or observe them only partially, a situation similar to the UN Declarations of Human Rights, which has still not been signed by all countries. Therefore, the EU, should make decisions in this area, as a de facto World Government, especially, when it becomes a Federation. Only then, sometime in the future, humans, although being far less intelligent than Superintelligence, will, hopefully, not be outsmarted, because that would not be the preference of Superintelligence.

Finally, we must resolve the ‘control vacuum’ in the period between now and the time when we may have a proper Global AI Governance Agency. We have no time to look for a perfect solution. We must have something in place right now. It appears that by default it should be the US Federal Drug Administration, which already considers applications for various brain implants. Among democratic countries, the USA is the most advanced country in AI and robot development and it is there where in the interim period a de facto global control over the most advanced AI agents should be made.