On this website, you will find top 7 existential risks, which Humanity faces right now. Among them, at the top of the list, is Superintelligence (Artificial General Intelligence). Somewhere in the middle of that list is Climate Change, which incidentally is not in any sense an immediate existential risk in comparison with bio pandemics or Superintelligence. The question is, what could force the world leaders to take the risk of Immature Superintelligence or other existential risks very seriously and act on them decisively right now.

Before I answer this question, let me refer to some recent and some historical events, when large civilizational catastrophes were looming and the decisions that the world leaders then took, impacted profoundly the fate of the world. I would call them existential risk-triggering decisions. They have two outcomes: they can prevent an existential risk becoming reality (risk-mitigating decision), or they can trigger it off (risk-triggering decision).

- Let me start with the WWII. In September 1938 the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain proudly showed the Munich Peace Accord, under which Hitler took over the Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland. That act of appeasement was thought to be enough to stop the European war, although it was already very clear at the time that Japan (invading China) and Italy (invading Abyssinia, today’s Ethiopia) colluded with Hitler so that fascism could take control of the entire world. We all know what happened later – 3% of the world population lost their lives. It was the Munich Accord that became the existential risk-triggering event, and which started a year later the global war by Germany attacking Poland in Gdansk.

Conclusion: For the very first time it was clear from the outset that the world may have entered a period of another global war. However, since there was no World Government with sufficient powers, which could rein in Hitler (the League of Nations was even weaker than today’s United Nations), it was only a matter of less than a year that the global war indeed started. - The second example is the post-war Europe. For most of the nations affected by the WWII, the experience was so horrible and profound that in many countries the most common graffiti at that time was “No more war!” The former main European adversaries: Germany, France, Italy and the Benelux first begun integrating their economies in 1952 (mainly the heavy industry) by forming the European Coal and Steel Community. Five years later that integration included common democratic values, which gave birth in 1957 to the European Economic Community, now the European Union.

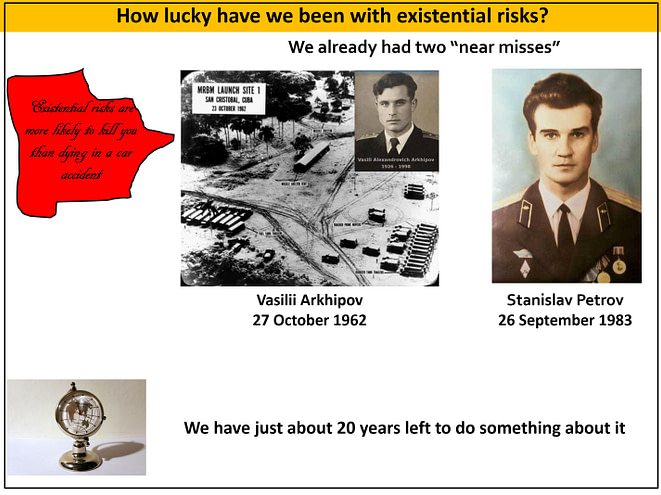

Conclusion: Europe has learnt a terrible lesson. Its existential risk-mitigating decision was to form the Steal and Coal Community in 1951, the precursor of the EU, rather than fight the Third WWW. Consequently, for the last 75 years, there was no war in Europe, apart from the Balkan war in the 1990’. That was only possible by having a relatively powerful European Commission and the European Council, a pseudo European Government – perhaps the precursor of the European Federation. - Another, a truly existential event, was the Cuban crisis in October 1962, when the world was just hours away from the break out of a global nuclear war. That event is still considered one of the most dangerous moments in human history. The global nuclear war did not happen because the Soviet Union agreed to withdraw their missiles from Cuba and the USA withdrew their nuclear missiles from Turkey. In the midst of a total chaos on 26th October 1962, the Soviet and American leaders took the right decision. A decade later, president Nixon and the first secretary of the Soviet Union – Brezhnev signed the SALT 1 Treaty, which froze the number of intercontinental missiles. The subsequent START 1 Treaty of 1991 led to a significant reduction of nuclear weapons. Against all the odds, a nuclear war has so far been avoided.

Conclusion: The fact that the world has not experienced a global nuclear war was not because the UN stopped that conflict. It was a decision made solely by two countries the USA and the Soviet Union but the consequences of that decision (in this case positive) impacted the whole civilisation. Here, the existential risk mitigating-decision that led to a long process of the reduction of nuclear missiles was to withdraw the Soviet missiles from Cuba and American missiles from Turkey, rather than fight a nuclear war. - The next event is the very recent Climate Change conference in Katowice in Poland on 16th December 2018. The conference coincided with the IPCC’s latest appeal to lower the CO2 emissions even further, so that the temperature growth will maximise at 1.5C, rather than 2C, as had been agreed in Paris. For me, the fact that the conference has agreed some concrete results, such as a unified system to measure the decarbonization of individual countries’ economies, is quite a success. That was only possible because some of the dangers of climate change are now very clear, such as the fires in California and Australia, or extreme hurricanes in North America. The dissemination of such information via TV and other media to billions of people, makes them more aware that climate change is real, and these extreme weather events could be just its first effects (still very minor). This in turn makes it easier for politicians to propose solutions that otherwise would have been rejected by the voters. However, please note, it took over 20 years from Rio to Paris to make the first Climate Change Agreement. Moreover, even the conference in Katowice can only be deemed a success in relative terms (that something after all has been agreed). In absolute terms, it is a failure because the world should be acting much faster and much more decisively, which requires us to make some quite painful, mainly financial, decisions.

Conclusion: The world has not been combating Climate Change properly because to solve such a global problem in an efficient way we need to act globally. But that requires a strong Global Government and not such a weak incoherent organisation like the United Nations. Although the signing of the Paris Accord in 2015, seems to be a significant step in the right direction, it has already been proven it is far inadequate and requires much more commitment from the signatories of the Treaty to accelerate the process of a gradual decarbonization of the world’s economy.

The man-made risks to which Humanity has been exposed so far have not been literally existential. However, if they had materialized, they would have been truly catastrophic. Immature Superintelligence falls into this category. Although it is not the only man-made existential risk, it is, excluding laboratory originated pandemics, the earliest and the most severe one. So, what are the other existential risks?

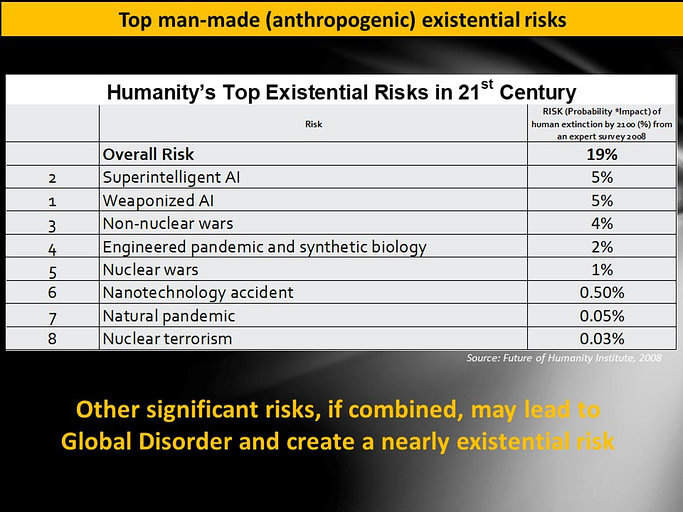

There are several organizations focused on identifying and reducing global catastrophic and existential risks such as Global Challenges Foundation, University of Oxford. They apply various methodologies for calculating existential risks, but none is failproof, nor is the data very rigid. Furthermore, not all risks are equal. They differ according to their impact and the probability of the risk materializing, which is calculated using the formula: Risk = Probability * Impact. Therefore, the risks calculated by various organizations, or well-known specialists in this area, vary significantly. For example, in 2008 the Future of Humanity Institute carried out a survey of the academics gathered at a conference discussing global existential risks and the likelihood of the most significant anthropogenic risks. They estimated that the combined risk of human extinction this century is 19%. That means, by the end of this century there is at least 19% chance that one, or several existential risks in the table below may materialize with the worst impact scenario – the end of the human species. In the period under consideration on this website, say over the next generation, such probability is about 5%. These are only the risks over which we have some control, mainly in political, military and social domains, such as nuclear wars, or artificial pandemics.

Assessing such risks is very difficult because of the interconnections (convergence) between them. Therefore, these numbers have to be really considered as indicative and prone to significant errors, mainly because of lack of hard data or insufficient understanding of the impact and the spread of a specific risk. The risks listed in the table may be very conservative indeed, as they do not even include the global warming, which an influential Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change calculates as 0.1% per year, leading to the likelihood of human extinction over a century to nearly 10%.

I cover these risks in more details in the subsequent sub-menus.

Comments