A nuclear war between the US and Russia was the chief apocalyptic fear of the late 20th century. That threat may have reduced but, with proliferation of nuclear weapons, there is still a risk of a conflict serious enough to cause a “nuclear winter” as the smoke in the stratosphere shuts out sunlight for months. That could put an end to civilised life regardless of the bombs’ material impact. Therefore, it is so difficult to assess the probability of global nuclear war ever taking place and even more difficult to tell if it will ultimately lead to a total collapse of civilisation. That’s why Global Challenges Foundation Report 2017 puts the risk between 1 and 9.5% (Global_Challenges_Foundation, 2017), which I have averaged to 5% and this is the level I would consider in further assessment of that risk.

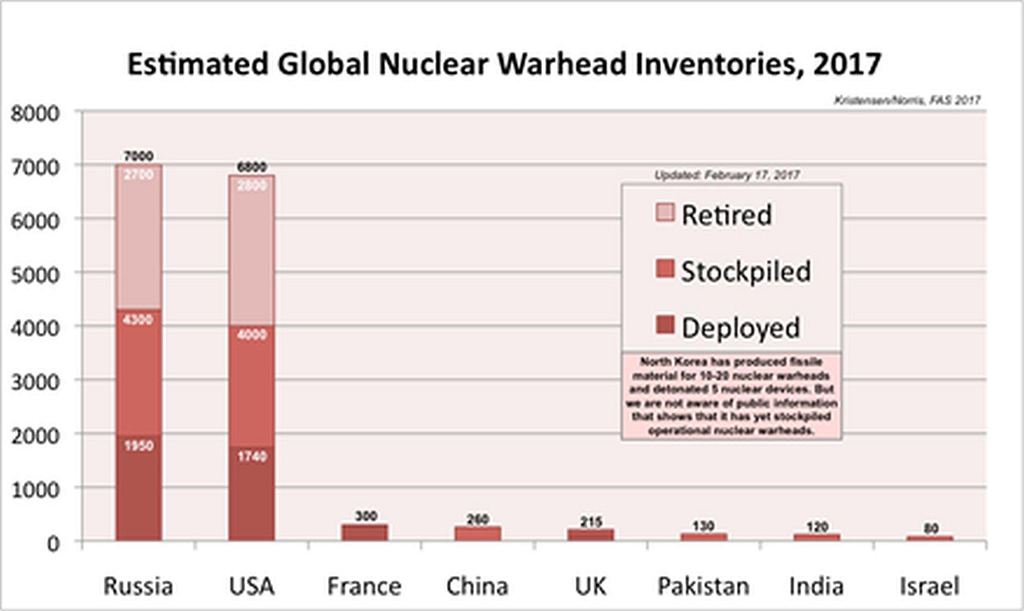

The scenarios that have been explored most frequently are nuclear warfare and doomsday devices. Although the probability of a nuclear war per year is slim, Professor Martin Hellman described it as inevitable in the long run. Inevitably there will come a day when civilization’s luck runs out (Wikipedia, 2016). During the Cuban missile crisis, U.S. President John F. Kennedy estimated the odds of nuclear war as being “somewhere between one out of three and even” (Avner Cohen). To put it in today’s context, the United States and Russia have a combined arsenal of 14,700 nuclear weapons, and there is an estimated total of 15,700 nuclear weapons in existence worldwide (Federation_of_American_Scientists, 28 April 2015).

While popular perception sometimes takes nuclear war as “the end of the world”, experts assign low probability to human extinction from nuclear war (Shulman, 5 Nov 2012). In 1982, Brian Martin estimated that a US–Soviet nuclear exchange might kill 400–450 million people directly, mostly in the United States, Europe and Russia and maybe several hundred million more through follow-up consequences in those same areas (Martin, 1982). Nuclear war could yield unprecedented human death tolls and habitat destruction. Detonating such a large amount of nuclear weaponry would have a long-term effect on the climate, causing cold weather and reduced sunlight that may generate significant upheaval in advanced civilizations (Physics).

The most recent scenarios give estimates on the climate change caused by a global nuclear war, without giving the number of casualties. One of these predicts that the explosion of 1,800 US – Russian warhead would cause a long-lasting cold period with a peak average global cooling of 4°C, whilst a larger scale nuclear war with over 3000 warheads (which is only about 35% of the current Russian nuclear stockpile – TC) would cause average cooling of 8°C. This is greater than the average cooling of 5°C experienced during the last ice age, so this would be a severe nuclear winter lasting a decade. Whilst an average cooling of only a few degrees may not sound very serious, the crucial impact is much longer periods of frost in winter and severe drought. There would be dramatically reduced growing seasons or even the impossibility of growing any crop as planned. Farming also relies upon supplies of fuel for mechanised planting and harvesting (Webber, 2018).

However, use of a nuclear weapon today would be much worse for two reasons:

- A typical modern nuclear weapon is now 8 to 80 times larger; modern society is much more reliant on vulnerable information technology and long distance supply routes for food and fuel.

- Modern society is heavily reliant on electricity to power central heating pumps, to provide water, information via TV, the internet and mobile phones. Nuclear strike will mean no water supply, no heating or lighting, no information, no mobile phone signal.

- Only a few days’ of food supply exists in regional distribution depots. The supply network would fail for multiple reasons: road blockages, communications breakdown, collapse of the banking system, destruction of ports.

International aid organisations and health bodies all agree that the tens of thousands of casualties from just one nuclear bomb would overwhelm all attempts to help the injured. As a result, there would be no hope of treatment for severe injuries including burns, broken bones and deep cuts from flying debris. With the intense levels of damage, huge fires would spread across all major towns and other targets lasting days to weeks. We now understand that these huge fires would cause long lasting climatic impacts at a global level, creating a nuclear winter. Realistically, after a large scale nuclear war, one must picture small groups of brutalised, traumatised people, violently thrown back into a pre-industrial age. Assuming that some people somewhere furthest from the bombs could initially survive this global catastrophe, any ‘recovery’ would surely be measured in hundreds of years. It has to be regarded a shocking indictment of our modern civilisation that current stockpiles of nuclear weapons are sufficient to cause such a global catastrophe (Webber, 2018).

Overall, the greatest possibility of a nuclear war today is in Asia. First, it is a significant potential for a nuclear conflict between India and Pakistan. At the heart of this conflict is, of course, the territorial dispute over the northern Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, which Pakistan says should be its territory. The reason behind a high risk of nuclear conflict between these two countries is the fact that India’s conventional capabilities are vastly superior to Pakistan’s. Consequently, Islamabad has adopted a nuclear doctrine of using tactical nuclear weapons against Indian forces to offset the latter’s conventional superiority. The latest climate models predict that the use of a just few tens to a hundred of the smaller nuclear weapons in the regional India-Pakistan scenario would cause severe frosts, reduced growing seasons, drought and famine lasting up to ten years across the entire northern hemisphere (Keck, 2017). This situation is similar to that between the U.S.-led NATO forces and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Numerically, the Soviet army was superior to that of NATO. Therefore, the United States, starting with the Eisenhower administration, turned to nuclear weapons to defend Western Europe from a Soviet attack

Another area of a potential conflict is between Israel and Iran. Although Iran apparently does not have nuclear weapons yet, but only some facilities, like plutonium generating centrifuges, it is highly likely, it can build them pretty soon despite the current oversight of the IAEA. Israel has at least once in the past try to stop the Iranian nuclear programme. In June 2010 an advanced computer worm called Stuxnet, was discovered, which is estimated that it might have damaged as many as 1,000 centrifuges (10% of all installed) in the Natanz enrichment plant (Institute_for_Science_and_International_Security, 2010).

Israel believes that Iran still continues to develop its nuclear programme deep in the mountains. Western defence experts point to the Iranian Fordo facility, which is located deep underground near the city of Qom, as a site that was immune to conventional air strikes. That is why Israeli leaders have concluded that conventional air strikes would be insufficient in curbing Iran’s nuclear program, leaving only a deployment of either tactical nuclear weapons or ground forces (Kalman, 2012).

Since summer 2017, the world’s attention has been firmly fixated on North Korea. On 4th July, 2017 North Korea launched its first intercontinental ballistic missile which could reach the mainland United States. That has led a few weeks later to a decision by the Hawaiian authorities announcing that they would revive a network of Cold War-era sirens, to alert the public in the event of a nuclear strike. Then on 3rd September 2017 North Korea tested a nuclear weapon far larger than any it had used. James Mattis, the U.S. Secretary of Defence, said it was seven times the size of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

That incident on its own may not have been that scary, had the potential damage only related to a direct impact zone (depending on the bomb size from a diameter of 20 km to 60-100 km). It would require the bomb to actually hit the ground. This seems to be a formidable barrier because on the re-entry the rocket’s head might heat up to about 2000C and explode before hitting the target. That’s why complicated thermal shields are needed, which N. Korea apparently does not have.

However, in October 2017, two members of the disbanded US congressional Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) commission said at the House Homeland Security subcommittee hearing that “a nuclear EMP attack from Kim Jong Un was the biggest threat to the US yet”. They added: “it could shut down the US electric power grid for an indefinite period, leading to the death within a year of up to 90 per cent of all Americans… A nuclear EMP attack of just a few bombs to cover the whole USA would be needed, to completely make out of use power grids and other critical infrastructures that make modern civilization, and life itself, possible. Eventually, millions would die from starvation, disease, and societal collapse” (Revesz, 2017).

Those who think that North Korea’s missiles and nuclear facilities can be wiped out in a preventive air strike would make a potentially disastrous error. N. Korea’s nuclear arsenal is dispersed and hidden throughout the country’s mountainous terrain. Failing to hit them all would leave some 10 million people in Seoul, 38 million people in the Tokyo vicinity and tens of thousands of US military personnel in northeast Asia vulnerable to missile attacks with either conventional or nuclear warheads. Even if the US managed to wipe out everything, Seoul would still be vulnerable to attacks from North Korea’s artillery (Isabel Reynolds, 2017).

The EMP effect of nuclear bombs has been known since the late 1950’. Today, it is almost certain that every country that has the capability to launch nuclear bombs, considers options to use EMP in several ways. The most ‘benign’ fact is that the number of immediate casualties could be relatively small if EMP bomb is exploded in the near space (above 100-150 km). The casualties would result mainly from airplane catastrophes, car accidents or hospitals. This is the most likely scenario if North Korea uses such a bomb, destroying not only electronic-dependent infrastructure in the USA but also in the neighbouring South Korea. The EMP impact would be comparable with the so-called neutron bomb built under President Reagan administration in 1981. Its main destructive power comes from radiation rather than from an electromagnetic pulse. It would have a similar effect, i.e. causing not too many direct human casualties but an almost complete immobilisation of the advancing army. In the 1980’ it was the Soviet army that would have been disabled within a few kilometres of the neutron bomb’s impact.

The second option might be to use EMP-type nuclear device in conjunction with other more ‘conventional’ weapons by one of the nuclear power states such as China, Russia, the USA, France or the UK. That is however, unlikely because it could have sparked of an all-out ‘hot’ nuclear global war, since each of these countries has part of its nuclear arsenal dispersed on the always-in the-air airplanes and on the submarines, which could deliver a retaliatory attack. That’s the same principles of mutual self-destruction that kept the world nuclear war free during the Cold War period.

The third option is launching such a bomb, with an objective to eliminate advanced military capabilities (e.g. nuclear sites, cyber spying equipment, etc.). That is quite likely in my view by one of these countries: Israel, Iran, India and Pakistan. That’s why the risk of a local nuclear incident is rated by experts as 50:50 in the next decade. A good example is Bill Perry who was a nuclear weapons expert serving as President Clinton’s Secretary of Defence. In April 2017 he said that the worst-case scenario would now mean nothing short of a total Armageddon. “An all-out general nuclear war between the United States and Russia would mean no less than the end of civilisation”. He believes that today’s global security threats are very different to what they once were. The most likely scenario for a nuclear attack would be if a terrorist group got hold of a small amount of enriched uranium, allowing them to make an improvised nuclear bomb. He estimates the chance of this happening within the next 10 years as even (Williams, 2017). Yes, the world still has plenty of nuclear weapons that could annihilate all life on Earth as this summary illustrates:

All the potential nuclear wars mentioned so far are deemed “local”. However, this is highly unlikely if the protégé of some of the ‘big party’ like China were in ultimate danger, in this case North Korea. The same may be said about Israel and Iran conflict, where the probability of serious military engagement, including the use of nuclear weapons, by Russia – supporting Iran, and America – supporting Israel, must be considered. Additionally, one has to include Russia’s current unpredictability in its territorial aims in Eastern and Central Europe. Like in the Cold War time, the Russians have superior man-power and also outnumber NATO in tanks. That might force NATO to use initially tactical, and if a local war gets out of control, strategic nuclear weapons starting a global nuclear conflict.

Comments